by STEPHANIE ESPINOZA

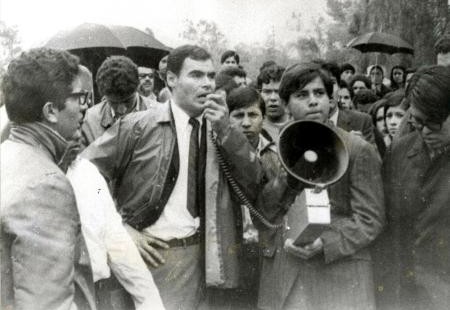

Sal Castro speaks on a megaphone during the 1968 school walkouts in East Los Angeles.

BAKERSFIELD – The first time I got to listen to Sal Castro speak was four years ago at UC Santa Barbara during my freshman year of college. Last month, I had the opportunity to hear him lecture again at Cal State Bakersfield, on the topic of education reform, along with professor Mario T. Garcia from UCSB.

Castro, an educator and lifelong Chicano activist, is most well known for his role in the East Los Angeles high school walkouts of 1968. Those historic walkouts were a defining moment of the Chicano movement. At its height, 15,000 mostly Latino students from schools throughout LAUSD left their classrooms to protest social discrimination and educational inequality between white and Latino students in the public school system.

The students back then had a long list of demands, which included: The establishment of bi-lingual and bi-cultural education programs in Latino majority schools; new textbooks and curriculum that would offer a more complete history of Latino contributions to society and injustices they’ve suffered; adequate representation of Latino staff and faculty at Latino majority schools; and the creation of review boards that would hold teachers accountable who have “a particularly high percentage of the total school dropouts” in their classrooms.

But how much has really changed for Latino students since those politically charged days in 1968? Maybe not as much as we’d like to believe.

Dropping out of high school, in particular, is still a big problem in the Latino community. Last year in California, the Latino high school graduation rate (67.7 percent) was far behind that of white (83.4 percent) and Asian (89.4 percent) students. In Southern Kern Unified, where Latinos make up the majority of students, that graduation rate drops down to a mere 52.1 percent.

So why, nearly 44 years after the walkouts, are Latinos still so much more likely to not finish high school? Castro suggests that the problem is as much psychological as it is economic: “The problem is that we are always considered strangers” in this land, he said, when in fact we are natives of this country, not foreigners.

Castro was quick to point out that California’s founding fathers had names like Julian Chavez, Manuel Dominguez, and Mariano Vallejo.

Throughout California, the city and street names are a reminder of our history here. Yet it’s a history that is continuously mispronounced, forgotten and misrepresented. No wonder we feel like strangers in our own country.

Back in high school, I can remember reading about Pancho Villa in my U.S. history textbook. He wasn’t mentioned as a Mexican revolutionary leader, who advocated for the poor and agrarian reform. Instead, he was referred to in the textbook as a bandido. A criminal. The bad guy.

On top of being left out of U.S. history, Latinos are also routinely blamed for our underachievement. From Garcia’s perspective, the problem is not that we don’t want to advance but that teachers come into the classroom with low expectations to begin with. As a result, their students don’t aspire to much.

Although Latinos are now going to college in greater numbers than ever before, college is still too often not an expectation or even part of the discourse in many low-income Latino homes. In order to change this, Castro went back to one of the original demands of the 1968 walkouts, challenging educators to incorporate bilingual and bicultural education in their classrooms in order to overcome the language barriers faced by students, as well as their parents.

Until all of that happens, until the vision that motivated the 1968 walkouts is realized, the struggle for educational equity will continue. Why? ¡Porque si se puede!

Jacob Simas contributed to this report