New America Media, News Report, Peter Schurmann

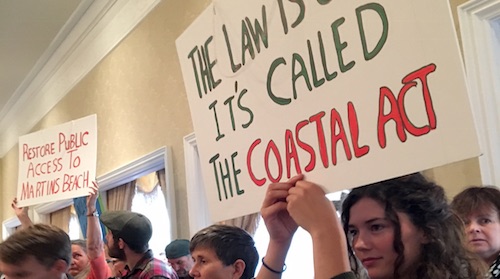

Above: Protestors gathered at a recent Coastal Commission hearing in Half Moon Bay, about 30 miles south of San Francisco, in October. (Photo by the author)

SAN FRANCISCO – On the 40 year anniversary of the California Coastal Act, a new Field Poll finds broad support for protecting the coast among a diverse majority of California residents even as many say issues of access are a problem.

Among other things, the findings highlight the central role the state’s 1,100 miles of coast plays in how all California residents see their state.

“The coast is essential to our identity as Californians,” says Jon Christensen with UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, which commissioned the poll.

The survey of 1800 voters in English and Spanish found that 90 percent of respondents said the condition of the coast is important to them personally, with 57 percent saying it is very important and 33 percent somewhat important. It also found that three out of four Californians visit the coast at least once a year, and that many visit more often.

The findings dovetail with a survey conducted over the summer of 1,000 beachgoers in Southern California, which found a wide swath of residents from around the state regularly visit the coast. That survey also found remarkable consistency in what people expect to find, with clean sand and water ranking highest, alongside amenities like restroom facilities and parking.

But despite the widespread affinity that many feel for the coast, issues of access remain a problem, particularly for low-income communities and communities of color around the state.

“The California Coastal Act makes this remarkable statement that the coast should be available to all Californians,” noted Christensen. “But we know that not all Californians find the coast as accessible.”

Passed in 1976, the Coastal Act governs the decisions of the Coastal Commission, which regulates development along the coast and is tasked with ensuring public access to it.

But according to the new poll, some 62 percent of California residents say accessing the coast is an issue, an increase from a similar survey by the Public Policy Institute of California in 2003 in which 53 percent cited access issues.

Time, cost and transportation were among the barriers cited by respondents. The Field Poll also found that African Americans were among those less likely to visit the coast, with 33 percent saying they visit less than once a year and citing an inability to swim as the key factor. Families earning more than $60,000 were also more likely to visit more often than families earning less than $40,000.

Phil King teaches at San Francisco State University and has spent the past 20 years researching the economics of coastal access. He says statewide disparities in housing costs are a big reason why more people say they aren’t visiting the coast.

“I think that’s the primary issue,” he says. “More people are moving inland … and farther away from the coast. And with the traffic, getting to the coast is not getting any easier,” says King.

The Coastal Act originally included provisions to ensure availability of affordable housing along the coastal zone, the narrow strip of coast that falls under the jurisdiction of the law. That provision was stripped in later legislation, and efforts to bring it back have so far not been successful.

Home prices along the coast, meanwhile, continue to soar. The median home price in San Francisco, for example, is more than eight times that of Bakersfield, while rents are similarly skewed. That, in turn, has fueled the migration inland, where cities such as Fresno, Bakersfield and San Bernardino saw an increase of 30,000 households earning less than $50,000 between 2011 and 2013, according to a report last year by the non-partisan Legislative Analysts Office.

“The really serious access issue is people getting from inland areas to the coast,” says King.

According to the poll, Central Valley voters are less likely to visit the coast, with 39 percent saying they visit less than once a year. In addition to time, a quarter of those who said they visit less than once a year cited the lack of affordable lodging as a reason.

“If you are driving two to three hours to come from Bakersfield at the height of summer … it’s like 110 degrees and you might want to actually stay for the weekend,” says Marce Gutierrez-Graudiņš, founder of Azul, a non-profit that works to connect Latino communities around the state to the coast and coastal issues. “But it’s so hard to find lodging.”

Gutierrez-Graudiņš explains the availability of affordable lodging correlates to the time investment that people in the Central Valley and other parts of inland-California make when they visit the coast. Some 44 percent of those who visit the coast less than once a year cited time as a key reason.

But she adds that barriers exist even for families who live closer to the beach.

As an example, she points to families in Los Angles where, “There are kids that have never seen the ocean and they are 20 minutes away. This has to do with there being little or no public transportation. It’s hard to actually get kids out to the beach.”

But she wants environmentalists, lawmakers and members of the Coastal Commission – which is tasked with ensuring the state meets the promise of access to the coast for all Californians under the Coastal Act – to understand that many of these communities remain very interested in coastal access.

“About a year ago I was working in east and southeast LA, and we had folks who couldn’t actually come to the Coastal Commission hearings … and yet we had grandmothers organizing rosarios for the ocean,” says Gutierrez-Graudiņš. “Just because people are not in the places that we typically think of as congregating areas for ocean stewards … doesn’t mean they don’t care or that they don’t do anything about it.”